Table Of Content

The entrance is barely discernible amidst the exterior’s jutting angles, which Gehry created from wood, glass, aluminum, and chain-link fencing. The old house’s apex peeks out from within this mix of materials, giving the impression that the house is consistently under construction. Gehry wrapped the house in layers of unfinished, frugal materials, including corrugated metal and chain-link, which reflected his relatively limited means at the time. This also allowed him to tap into a fascination with everyday materials that had begun when he was a child spending time in his grandparents’ hardware store. Both corrugated metal and chain-link were considered ugly industrial fixtures in the L.A. Inspired by contemporary sculpture, Gehry embraced the challenge of proving that art could be made out of anything, even chain-link.

Watch film

In 1977, Frank and Berta Gehry bought a pink bungalow that was originally built in 1920. Gehry wanted to explore the materials he was already using — metal, plywood, chain link fencing, and wood framing. In 1978, he chose to wrap the outside of the house with a new exterior while still leaving the old exterior visible. He hardly touched the rear and south facades, and to the other sides of the house, he wedged in tilted glass cubes. And we wanted two separate vanities, that seemed to be the biggest issue with the girls sharing a bathroom before.

Filming

The resulting soundtrack, like the film itself, attempts to span the generation gap by putting each generation’s outlook into paradoxical dialogue. Though controversial, the house attracted important clients, which gave Gehry the freedom to work on grander projects than the modest homes he had designed up to that point. The second renovation of his Santa Monica home, in 1991–92, was undertaken to accommodate the changing needs of the Gehry family and included the addition of a lap pool, the conversion of the garage into a guesthouse, and increased landscaping for privacy. Some of the exposed wood frames were removed or covered over, and many lamented a loss of edge. However, the house became more open and comfortable for Gehry and his family, and the increased finish, more delicate materials, and greater coherence reflected. When talking about the house’s design, Gehry also references the sense of movement in Dada artist Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase and the unfinished quality of Abstract Expressionist artist Jackson Pollock’s paintings, which Gehry says look as though the paint was just applied.

House (1977 film)

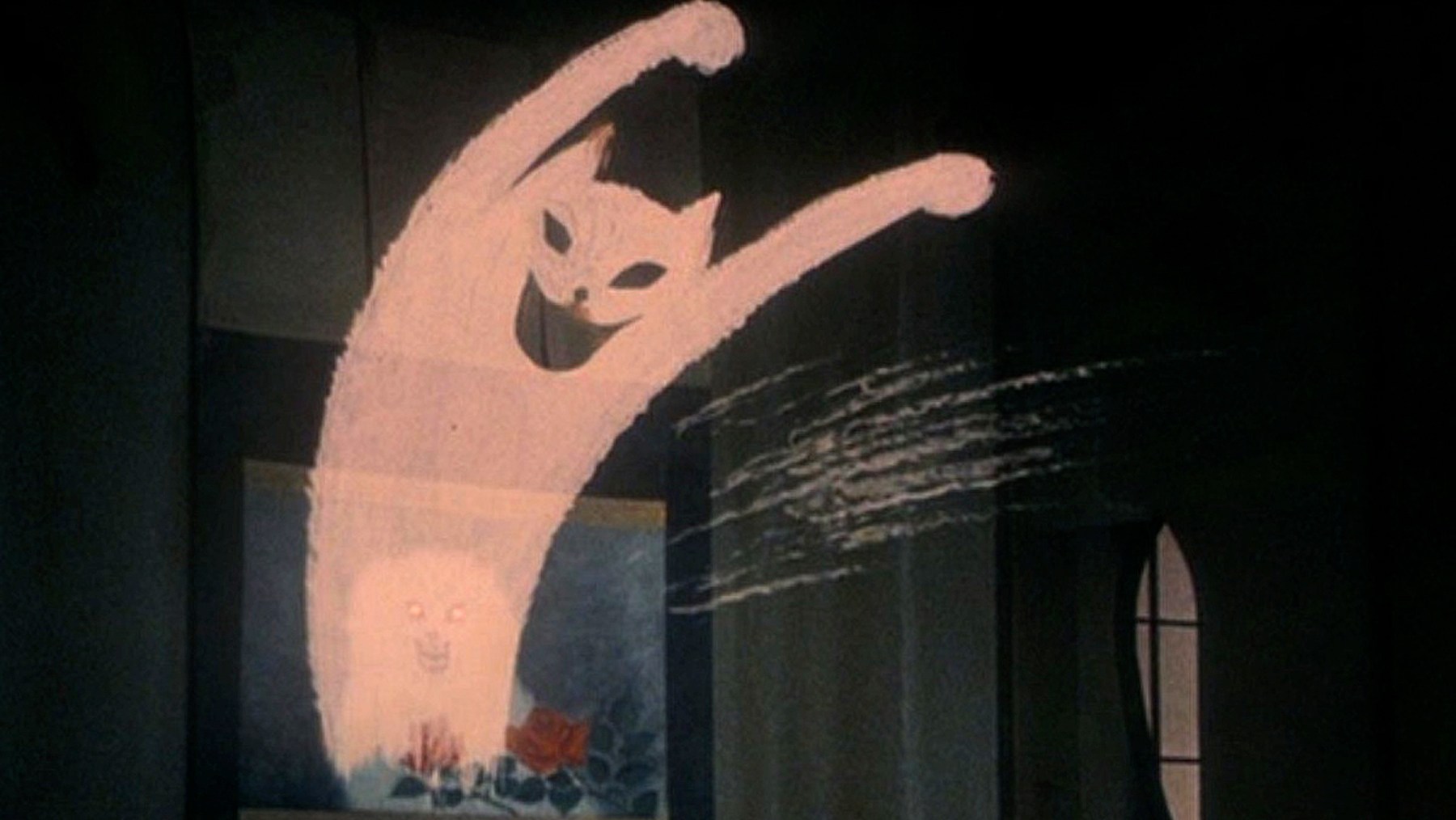

Although the undercurrent of incredible sadness that surges through House ages us just a bit, Obayashi still sends us out on one final swell of fantasy, forgiving us our naïve need to believe in beauty even as it walks hand in hand with his damning excoriation of humanity. There’s joy amidst fear, and there will be loss in our future, and from the cinematic overlap of these truths emerges Obayashi’s “story of love.” Like a leitmotif, no matter what form it takes, we all eventually hear the same melody. Although Obayashi is quick to textualize his observations about the differences in perception between younger and older Japanese moviegoers—“it’s like a cotton candy! ” one of the girls coos early in the film at footage of an atomic detonation—his intentions in doing so aren’t initially clear. Are the girls simply callous, or is 32 years of distance from unprecedented horror enough to justify their lighthearted attitudes?

Beautiful, practical – a house any family would love living in (

At times House almost feels like a children’s film, its opening scenes featuring broad slapstick, a cheesy pop song and endless girlish giggling. Despite Auntie’s hermetic lifestyle and tragic wartime backstory (her fighter-pilot fiancé never returned to marry her), she is far from the Miss Havisham type. The girls find both her and the titular house perfectly charming upon their arrival. But with spooky happenings around the house and the visiting party starting to shrink in numbers, both home and homeowner reveal their sinister true natures.

HOUSE (NOBUHIKO OBAYASHI, 1977) - Dazed

HOUSE (NOBUHIKO OBAYASHI, .

Posted: Mon, 22 Apr 2024 11:16:00 GMT [source]

Although all of House’s music is evocative, its leitmotif is the Rosetta Stone to understanding its complex attitude toward romance, youth, and the specter of post-war Japan that looms over them. It’s initially used as a malleable, expressionistic representation of how the girls are feeling at any point in time, often warm and jovial with a strongly nostalgic character. At the halfway point, however, the leitmotif enters the film’s diegesis in the form of a music box, changing from an emotional signpost into an icon of wartime grief. Its appearance signals a turn in both the girls’ understanding of their dire circumstances and the viewer’s understanding of how House uses music to create a false sense of comfort. Through Godiego’s young hands, Obayashi inspires feelings of romantic warmth and hope as we get to know the girls, only to cast doubt on the meaning and validity of those feelings once the horrors of Auntie’s house obliterate their youthful illusions. One wing comprises living room, master bedroom and bath, study/guest room; the other houses all the daytime living spaces plus two children’s bedrooms.

Love, Lies, and Leitmotifs

Upstairs in the house, Kung Fu and Prof find Gorgeous wearing a bridal gown, who then reveals her aunt's diary to them. Kung Fu follows Gorgeous as she leaves the room, only to find Sweet's body trapped in a grandfather clock, which starts bleeding profusely. Panic-driven, the remaining girls barricade the upper part of the house while Prof, Fantasy and Kung Fu read the aunt's diary. After a tour of the home, the girls leave the watermelon in a well to keep it cold. When Fantasy goes to retrieve the watermelon from the well, she finds Mac's disembodied head, which flies in the air and bites Fantasy's buttocks before she escapes.

Dark paneled walls and warm brick fireplace wall create an inviting background for traditional furnishings updated with lively plaids and prints. By design, this spacious one-level house opens graciously from a center hall that links two carefully planned rectangular living areas. Even after the flesh perishes, one can live in the hearts of others together with the feelings one has for them.

In “Constructing a House,” Obayashi mentions that the actresses “belonged to a younger generation that found it easier to express emotion through chords, melodies, and rhythms than through words. Nobuhiko Obayashi’s House was released in Japan in 1977 to a highly polarized reaction. To the lifelong devotee of classical Japanese cinema, it was indeed sacrilegious, a mutant child born of American genre bombast, anime-style hyperkinesis, and manic psychedelia. Despite the protestations of the old guard, though, the movie was a hit, and in the ensuing decades, Obayashi’s esteem has only grown. There is, however, something underpinning all the madness, a quietly melancholic undercurrent that ultimately elevates the film.

Obayashi’s darkly comic fable tells the story of seven schoolgirls, each of them named for their defining attribute, à la Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). The pretty but pensive Gorgeous is joined by Prof (brainy), Kung Fu (violent), Fantasy (a daydreamer), Sweet (homely), Melody (musical) and the ever-eating Mac (short for ‘stomach’) on a summer trip to her aunt’s creaky old house in the countryside. The sumptuous master bedroom (above) in the American Home of 1974 has serenely Oriental touches. Many thanks to Annie of Annie M Designs — not only did she photograph the home, but also she recommended the homeowners contact us for this story. In the spacious master bedroom, ripe peach is the luscious color that envelopes the setting. Behind seating area sliding glass doors that open to patio provide a sunny daytime view.

It isn’t until the final two survivors find and read Auntie’s diary that they recognize not only the tremendous loss and betrayal that the war left in its wake, but how the shadow of that loss has deformed into the specters and nightmares that now assail them. Their only hope as they float upon an ocean of blood, out of options and no exit in sight, is that Mr. Togo might finally arrive at the house just in time to save them. This lilting music-box melody is the prime transformative catalyst not only for Gorgeous, but for actress Kimiko Ikegami. Without the benefit of seeing the visual effects that accompany her possession, Ikegami has only the leitmotif to inform her new thousand-yard stare, the flat affect that crawls into her voice, her slow shuffle down the stairs and to the telephone.

The piano swallows Melody whole, and her remaining disembodied fingers plunk out a final few bars of the leitmotif before hitting a sour note and being crushed under the piano lid. If Obayashi’s “younger generation” is as musically inclined as he claims, the message must be as unequivocal to them as it is to us, especially when communicated through melodies crafted by their own cohort. This is one of the many elements that makes Gorgeous’ possession so powerful. At the midpoint of the film, she enters Auntie’s room and sits at a vanity adorned with tokens of youthful beauty—makeup, fancy hairpieces, a photo of a lover long since passed.

Kung Fu's legs manage to escape and damage the painting of Blanche on the wall, which in turn kills Blanche physically. Prof tries to read the diary, but a jar with teeth pulls her into the blood, where she dissolves. Gorgeous appears as her aunt in the reflection in the blood and then cradles Fantasy.

No comments:

Post a Comment